Smoking Cessation Programs For Teens and Adolescents 3.0 CE Hours

Course Objectives:

- Describe the health impact of smoking

- The role of the medical professional in tobacco education

- Identify factors that influence adolescents to smoke

- Indicate strategies to prevent and eliminate teenage smoking

- Resources and research

INTRODUCTION

This course will provide a great deal of practical education on the issue of young people and smoking. In order to facilitate your work as Respiratory Therapists, there are a high number of practical strategies, articles, and downloadable documents that you can put into your toolbox. To educate young smokers, one needs to have a lot of different strategies. Educational programs need to speak to them as young people. They understand and process information differently than adults, and they are subject to different stressors. Many young people today don’t see the issue of their future health as being problematic. They mistakenly think they can quit at any time. But, the longer one continues to smoke, the harder it becomes. This is common premise in healthcare, but not necessarily a principle that young people understand. In this module, the practical strategies, research articles, and other materials will enable you to put together your own programs that meet the specific needs of your patients.

THE HEALTH IMPACT OF SMOKING

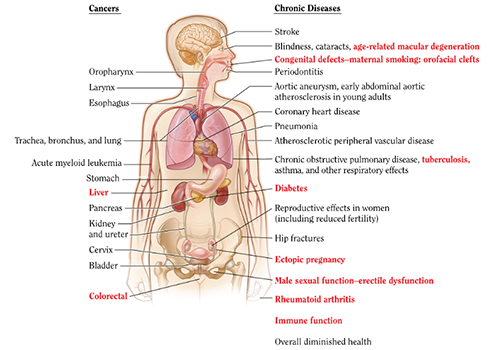

For decades, the habit of smoking was glamorized by films, television, and smoking. The image of Humphrey Bogart smoking a cigarette as he spoke some of his iconic lines in Casablanca probably inspired hundreds, if not thousands of young men to do the same. Then, media advertising kicked in with tobacco campaigns which glorified the smoker. Images of tough men on a horse holding a cigarette gave tobacco smoke a great name. Even with the insidious damage this was doing to millions of people, tobacco campaigns continued. Today, cigarette packages come with severe warnings, yet people continue to smoke, even though they know the serious dangers of tobacco. The health impact of smoking is a huge topic today as many cities have begun campaigns to ban indoor smoking to prevent the dangers of second-hand smoke. Pregnant women are warned not to smoke cigarettes, as this can cause serious harm to their unborn child. How can we possibly understand the huge health impact of smoking? Let’s begin with an image provided to us by the Center for Disease Control:[1]

Smoking literally affects every organ in the body. Just as with other harmful substances, the effects are cumulative over time. So, someone might believe they’re fine because they haven’t noticed anything wrong. But, the problems sneak up on them, and will eventually inflict a great deal of damage on the body. The primary problem is that all of these health effects are inter-related. When the body has to cope with one serious illness, then the rest of the body has to work harder to cope.

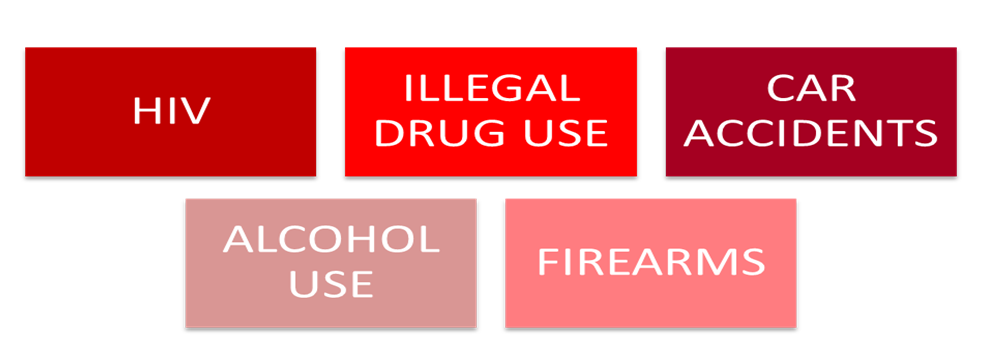

The frightening reality of smoking is that it causes more deaths than all the following combined:

The CDC[2] lays out the following information which provides a very clear picture of the damage of tobacco smoke:

Cardiovascular Disease:

- Smoking causes stroke and coronary heart disease—the leading causes of death in the United States

- Even people who smoke fewer than five cigarettes a day can have early signs of cardiovascular disease.

- Smoking damages blood vessels and can make them thicken and grow narrower. This makes your heart beat faster and your blood pressure go up. Clots can also form.

- A heart attack occurs when a clot blocks the blood flow to your heart. When this happens, your heart cannot get enough oxygen. This damages the heart muscle, and part of the heart muscle can die.

- A stroke occurs when a clot blocks the blood flow to part of your brain or when a blood vessel in or around your brain bursts.

- Blockages caused by smoking can also reduce blood flow to your legs and skin

Respiratory Disease:

- Lung diseases caused by smoking include COPD, which includes emphysema and chronic bronchitis.

- Cigarette smoking causes most cases of lung cancer.

- If you have asthma, tobacco smoke can trigger an attack or make an attack worse.

- Smokers are 12 to 13 times more likely to die from COPD than non-smokers.

Cancer:

- Bladder

- Blood (acute myeloid leukemia)

- Cervix

- Colon and rectum (colorectal)

- Esophagus

- Kidney and ureter

- Larynx

- Liver

- Oropharynx (includes parts of the throat, tongue, soft palate, and the tonsils)

- Pancreas

- Stomach

- Trachea, bronchus, and lung

Other Health Risks:

- Pre-term babies

- Stillbirths

- Low birth weight

- Sudden Infant Death Syndrome

- Ectopic pregnancy

- Orofacial clefts in infants

- Reduction in fertility

- Risks for birth defects

- Miscarriages

- Lower bone density

- Increased risk for cataracts

- Age-related macular degeneration

- Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- Inflammations

- Reduced immune function

- Rheumatoid arthritis

The unfortunate reality is that not only smokers face serious health risks, but second-hand smoke has now been identified as a major health problem. Some of the health problems faced by people who are subjected to second-hand smoke are:

- Heart problems

- Lung cancer

- Breathing problems (like more severe asthma)

- Excessive coughing

- Throat irritation

- Premature death

Children are especially vulnerable to second-hand smoke, and face many health complications as a result. They include the following:

- Respiratory illnesses

- More frequent and more severe asthma attacks (among children with asthma)

- Ear infections

- Phlegm, wheezing, and breathlessness

- Decreased level of lung function

THE ROLE OF THE MEDICAL PROFESSIONAL IN TOBACCO EDUCATION

The medical professional can play three specific roles in tobacco cessation education:

- Prevention (helping to keep non-smokers from starting)

- Cessation (helping people who now smoke to quit, and preventing relapse)

- Protection (protecting non-smokers from second-hand smoke and other harmful effects of tobacco)

Of these three strategies, prevention is the most important. medical professional’s can educate their patients about the importance of living a healthy life. This is especially so if their patients already have a breathing disorder. Second, the medical professional plays a significant role in teaching their patients how to enhance the quality of their life by quitting smoking. As health professionals are in a unique position to assist smokers. Many smokers do want to quit, but the relapse rate is very high due to the addictive nature of tobacco, and other pressures such as social or peer pressure. In most smoking cessation programs, a quit rate of between 15 and 20% is considered a success. It is an unfortunate reality that most smokers attempt to quit several times before they finally succeed. Smoking cessation counseling is widely recognized as an effective clinical practice. Even a brief intervention by a health professional significantly increases the cessation rate. A smoker’s likelihood of quitting increases when he or she hears the message from a number of health care providers from a variety of disciplines.

Here are the guiding principles that the medical professional should follow:

- The medical professional can take a leadership role in smoking cessation and prevention. They have the knowledge and expertise to help their patients quit smoking.

- To help a patient quit smoking is one of the most important services a health care provider can offer.

- A comprehensive approach to smoking cessation is important (e.g. assessment, counselling, pharmacotherapy, ongoing support, relapse prevention strategies). Therefore, the medical professional should avail themselves of all the knowledge their team has to offer in terms of helping the patient to quit smoking.

- The medical professional should always use a collaborative multidisciplinary approach.

- Each medical professional will bring their own unique knowledge and expertise to advance an overall strategy.

- The patient/client is an active partner in the smoking cessation process.

- The medical professional can take an empowered approach and ask each patient about their smoking status when appropriate and document it.

- medical professional’s should take part in tobacco cessation education training when and where appropriate

FACTORS THAT INFLUENCE TEENS AND ADOLESCENTS TO SMOKE

Irrespective of the dangers, many teens and adolescents and teens love to smoke. Here are some of the factors which continue to influence young people today.

- Peer influence:This is the most common reason that kids and teens, especially girls, start to smoke. Kids whose friends smoke are more likely to start smoking, as it gives them a sense of belonging. Adolescents and teens are in a state of constant change. Their bodies are growing, and their hormones are developing. They see some of the other kids smoke, and imagine that it will be ‘cool’ to be among those kids. Young people desperately want and need to be accepted. All too often, they will take unnecessary and dangerous risks in order to feel that sense of belonging, and hopefully be popular among their peers.

Another aspect of peer influence is the pressure for young girls to look good. This is almost always interpreted as being thin. Far too many young girls are using cigarettes to refrain from eating, and also diminish their appetite. This has resulted in an alarming number of young girls developing the dangerous condition known as ‘Anorexia Nervosa’.

- Adult smoking:When kids and teens see adults, especially their parents or other family members, smoke, they will be more likely to smoke because they will perceive smoking as normal behaviour and something that is grown-up and mature. Far too many adults continue to smoke in front of their children. Even though the warnings are clear, and the danger is obvious, these young people are subjected to second-hand smoke. Some parents even encourage their children to smoke; although the reasons why they would do so are unclear.

- Coping with stress:Just like adults, kids and teens can use smoking to relieve stress. Nicotine inhaled by cigarettes rapidly activates the reward and pleasures areas of the brain, creating positive feelings and sensations. Young people today are exposed to a huge number of stressors that weren’t present even one or two generations ago. The world has many dangers today that are causing them to feel uncertain and even unhappy. Many kids come from abusive families, or socio-economic circumstances that cause them to feel unstable and uncertain. Smoking seems to them an easy to help them cope with these stressors.

- Advertising: Unfortunately, tobacco companies often gear marketing towards teens and children. They are a key demographic: most people who become regular smokers start smoking in their teens. Irrespective of the dangers, there are still tobacco commercials. While they’re not as present as they used to be, the advertising continues. Young minds are often highly susceptible to these messages.

- Media:When kids and teens see movies and television shows where actors smoke, they are more likely to try smoking since they often look up to actors and want to emulate their behaviour. Far too many well-known individuals smoke: actors, musicians, models, and other celebrities. When they’re seen smoking, young people think of this as an okay thing to do. They can’t imagine that these celebrities would willingly do themselves any harm. The media is a potent atmosphere for encouraging young people to smoke.

STRATEGIES TO PREVENT AND ELIMINATE TEEN AND ADOLESCENT SMOKING

To begin with, medical professional’s need to have the facts on hand. Here are eleven facts about teenage smokers:

- 90% of smokers began before the age 19.

- Every day, almost 3,900 adolescents under 18 years of age try their first cigarette. More than 950 of them will become daily smokers.

- Tobacco use is the leading cause of preventable death in the United States. Create handmade postcards encouraging smokers to quit.

- About 30% of teen smokers will continue smoking and die early from a smoking-related disease.

- Teen smokers are more likely to have panic attacks, anxiety disorders and depression.

- Studies have found that nearly all first use of tobacco takes place before high school graduation.

- Approximately 1.5 million packs of cigarettes are purchased for minors annually.

- On average, smokers die 13 to 14 years earlier than nonsmokers.

- According to the Surgeon General, teenagers who smoke are 3 times more likely to use alcohol, 8 times more likely to smoke marijuana, and 22 times more likely to use cocaine.

- In fact, hookah smoke has been shown to contain concentrations of toxins, such as carbon monoxide, nicotine, tar, and heavy metals that are as high, or higher, than those that are seen with cigarette smoke.

- Cigarette smokers are also more likely to get into fights, carry weapons, attempt suicide, suffer from mental health problems such as depression, and engage in high-risk sexual behaviors.

To educate young smokers, and encourage them to enter into a cessation program, medical professional’s also need to understand the factors related to addiction.

Concepts of nicotine addiction have evolved over the 40 years since the Surgeon General’s report first reviewed smoking. For example, in 1964 the Report of the Advisory Committee to the Surgeon General classified tobacco as “a habituation rather than an addiction” and that preventing the psychogenic drive of the habit was more important than using nicotine substitutes. Concepts about the physiology of nicotine addiction have since evolved. For example, in 1979 the Report of the Surgeon General cited nicotine as “a powerful addictive drug.” And in 1988 the Report of the Surgeon General on The Consequences of Smoking: Nicotine Addiction concluded:

- Cigarettes and other forms of tobacco are addicting.

- Nicotine is the drug in tobacco that causes addiction.

- Pharmacologic and behavioral processes that determine tobacco addiction are similar to those that determine addiction to drugs such as heroin and cocaine[3].

medical professional’s need to be able to explain to young people how they became addicted to begin with, the consequences of continuing to smoke, and the healthy strategies they can use to quit smoking. Nicotine addiction is much like other addictive substances; the person has to wean themselves off the substance in a healthy, graduated process. There are new resources that medical professional’s can use to help young people to quit smoking on a permanent basis. The two-fold process to quit smoking can be understood as these two inter-related strategies:

Pharmacologic Interventions:

This is generally understood as “nicotine replacement therapy”. Some of the medications used are:

- Sustained-Release Bupropion

- Clonidine

- Nortriptyline

Alternative therapies that can be used in conjunction with medications include:

- Acupuncture

- Homeopathy

- Herbal medicines

- Exercise

- Aversive therapy

Behavioral Interventions:

Behavioral interventions can vary quite widely. There are numerous counseling techniques and approaches that have been known to be extremely helpful with addictions. Some of the basic steps in a tobacco cessation program are laid out as follows:

- Advise the patient to quit

- Provide clear, strong, and personalized information

- Assess the potential of support

- Assist in quite attempts and help with a quit plan

- Set a quit date

- Enlist (if possible) the support of family and friends

- Anticipate challenges

- Remove all tobacco products from the environment

- Provide problem-solving strategies

- Stress abstinence

- Anticipate and educate patient regarding triggers

- Keep reviewing the relationship of tobacco use in the person’s life

- Recommend pharmacotherapy

- Provide supplementary education and resource materials

Here are some excellent educational materials for use with teens who smoke:

- Tobacco-Free Kids Youth Advocacy Initiatives

http://www.kickbuttsday.org/for-youth-advocates/advocacy_initiatives/

- Youth Tobacco Cessation: A Guide for Making Informed Decisions

http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/quit_smoking/cessation/youth_tobacco_cessation/index.htm

- Youth Tobacco Prevention

http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/youth/index.htm

- Smoking and Tobacco Use (CDC)

http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/

- Helping Young Smokers Quit: Identifying Best Practices for Tobacco Cessation:

http://www.helpingyoungsmokersquit.org/

- Youth Tobacco Cessation Collaborative

http://www.youthtobaccocessation.org/index.html

- I Quit

http://www.smokingstinks.org/quitkit/index.html

- Teen Smoke Free

http://teen.smokefree.gov/

- Learn to Live Healthy

http://www.learntolivehealthy.org/ltl_pdf/roadmaptoquitting.pdf

- Helping Young Smokers Quit

http://www.helpingyoungsmokersquit.org/

- The National Cancer Institute

http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/tobacco/smoking

- Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults (From The Surgeon General of the U.S.)

http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/2012/consumer_booklet/pdfs/consumer.pdf

RESOURCES AND RESEARCH

From the Surgeon General of the U.S.: Your Guide to the 50th Anniversary Surgeon General’s Report on Smoking and Health

- http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/50-years-of-progress/consumer-guide.pdf

In 2009, President Obama signed the following into law: The "Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act" which presents the following[4]:

- Ban all outdoor tobacco advertising within 1,000 feet of schools and playgrounds

- Ban all remaining tobacco-brand sponsorships of sports and entertainment events

- Ban free giveaways of any non-tobacco items with the purchase of a tobacco product or in exchange for coupons or proof of purchase

- Limit advertising in publications with significant teen readership as well as outdoor and point-of-sale advertising, except in adult-only facilities, to black-and-white text only

- Restrict vending machines and self-service displays to adult-only facilities

- Require retailers to verify age for all over-the-counter sales and provide for federal enforcement and penalties against retailers who sell to minors

The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General[5]

(This report provides medical professional’s with a wealth of facts to provide young people about the dangers of smoking)

This is the 32nd tobacco-related Surgeon General’s report issued since 1964. It highlights 50 years of progress in tobacco control and prevention, presents new data on the health consequences of smoking, and discusses opportunities that can potentially end the smoking epidemic in the United States. Scientific evidence contained in this report supports the following facts:

The century-long epidemic of cigarette smoking has caused an enormous, avoidable public health catastrophe in the United States.

- Since the first Surgeon General’s report on smoking and health was published 50 years ago, more than 20 million Americans have died because of smoking.

- If current rates continue, 5.6 million Americans younger than 18 years of age who are alive today are projected to die prematurely from smoking-related disease.

- Most of the 20 million smoking-related deaths since 1964 have been adults with a history of smoking; however, 2.5 million of those deaths have been among nonsmokers who died from diseases caused by exposure to secondhand smoke.

- More than 100,000 babies have died in the last 50 years from Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, complications from prematurity, complications from low birth weight, and other pregnancy problems resulting from parental smoking.

- The tobacco epidemic was initiated and has been sustained by the tobacco industry, which deliberately misled the public about the risks of smoking cigarettes.

Despite significant progress since the first Surgeon General’s report, issued 50 years ago, smoking remains the single largest cause of preventable disease and death in the United States.

- Smoking rates among adults and teens are less than half what they were in 1964; however, 42 million American adults and about 3 million middle and high school students continue to smoke.

- Nearly half a million Americans die prematurely from smoking each year.

- More than 16 million Americans suffer from a disease caused by smoking.

- On average, compared to people who have never smoked, smokers suffer more health problems and disability due to their smoking and ultimately lose more than a decade of life.

- The estimated economic costs attributable to smoking and exposure to tobacco smoke continue to increase and now approach $300 billion annually, with direct medical costs of at least $130 billion and productivity losses of more than $150 billion a year.

The scientific evidence is incontrovertible: inhaling tobacco smoke, particularly from cigarettes, is deadly. Since the first Surgeon General’s Report in 1964, evidence has linked smoking to diseases of nearly all organs of the body.

- In the United States, smoking causes 87 percent of lung cancer deaths, 32 percent of coronary heart disease deaths, and 79 percent of all cases of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

- One out of three cancer deaths is caused by smoking.

- This report concludes that smoking causes colorectal and liver cancer and increases the failure rate of treatment for all cancers.

- The report also concludes that smoking causes diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis and immune system weakness, increased risk for tuberculosis disease and death, ectopic (tubal) pregnancy and impaired fertility, cleft lip and cleft palates in babies of women who smoke during early pregnancy, erectile dysfunction, and age-related macular degeneration.

- Secondhand smoke exposure is now known to cause strokesin non-smokers.

- This report finds that in addition to causing multiple serious diseases, cigarette smoking diminishes overall health status, impairs immune function, and reduces quality of life.

Smokers today have a greater risk of developing lung cancer than did smokers in 1964.

- Even though today’s smokers smoke fewer cigarettes than those 50 years ago, they are at higher risk of developing lung cancer.

- Changes in the design and composition of cigarettes since the 1950s have increased the risk of adenocarcinoma of the lung, the most common type of lung cancer.

- Evidence suggests that ventilated filters may have contributed to higher risks of lung cancer by enabling smokers to inhale more vigorously, thereby drawing carcinogens contained in cigarette smoke more deeply into lung tissue.

- At least 70 of the chemicals in cigarette smoke are known carcinogens. Levels of some of these chemicals have increased as manufacturing processes have changed.

For the first time, women are as likely to die as men from many diseases caused by smoking.

- Women’s disease risks from smoking have risen sharply over the last 50 years and are now equal to men’s for lung cancer, COPD, and cardiovascular diseases. The number of women dying from COPD now exceeds the number of men.

- Evidence also suggests that women are more susceptible to develop severe COPD at younger ages.

- Between 1959 and 2010, lung cancer risks for smokers rose dramatically. Among female smokers, risk increased 10-fold. Among male smokers, risk doubled.

Proven tobacco control strategies and programs, in combination with enhanced strategies to rapidly eliminate the use of cigarettes and other combustible, or burned, tobacco products, will help us achieve a society free of tobacco-related death and disease.

- The goal of ending tobacco-related death and disease requires additional action.

- Evidence-based tobacco control interventions that are effective continue to be underused. What we know works to prevent smoking initiation and promote quitting includes hard-hitting media campaigns, tobacco excise taxes at sufficiently high rates to deter youth smoking, and promote quitting, easy-to-access cessation treatment and promotion of cessation treatment in clinical settings, smoke-free policies, and comprehensive statewide tobacco control programs funded at CDC-recommended levels.

- Death and disease from tobacco use in the United States is overwhelmingly caused by cigarettes and other burned tobacco products. Rapid elimination of their use will dramatically reduce this public health burden.

- New “end-game” strategies have been proposed with the goal of eliminating tobacco smoking. Some of these strategies may prove useful for the United States, particularly reduction of the nicotine yield of tobacco products to non-addictive levels.

Research Articles:

- Smoking Cessation Treatment for Adolescents

In The Journal of Pediatric Pharmacology Therapy: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3042263/

Julie P. Karpinski, Erin M. Timpe, and Lisa Lubsch

- Motivating Adolescent Smokers to Quit through a School-Based Program: The Development of Youth Quit2Win

In Adolescent Smoking and Health Research:

http://www.tobaccoprogram.org/pdf/Adolescent-Smoking&Health-08.pdf

Tyree Oredein, Jonathan Foulds, Nancy Speelman-Edwards and Jyoti Dasika

- Risk Factors for Smoking Behaviors Among Adolescents

In The Journal of School Nursing August 2014,30: 262-271

Sung Suk Chung and Kyoung Hwa Joung

- Gender Differences in Reasons to Quit Smoking Among Adolescents

In The Journal of School Nursing, August 2014; vol. 30, 4: pp. 303-308.

Laura L. Struik, Erin K. O’Loughlin, Erika N. Dugas, Joan L. Bottorff, and Jennifer L. O’Loughlin

Current Research into Smoking Cessation:

- Pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation: current advances and research topics.

In CNS Drugs. 2011 May;25(5):371-82. doi: 10.2165/11590620-000000000-00000.

Raupach T, van Schayck CP

Abstract: Promoting smoking cessation is among the key medical interventions aimed at reducing worldwide morbidity and mortality in this century. Both behavioral counselling and pharmacotherapy have been shown to significantly increase long-term abstinence rates, and combining the two treatment modalities is recommended. This article provides an update on pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation in the general population.

- Nicotine vaccines to assist with smoking cessation: current status of research

In Drugs. 2012 Mar 5;72(4):e1-16. doi: 10.2165/11599900-000000000-00000.

Raupach T, Hoogsteder PH, and Onno van Schayck CP.

Abstract: Tobacco smoking causes cardiovascular, respiratory and malignant disease, and stopping smoking is among the key medical interventions to lower the worldwide burden of these disorders. However, the addictive properties of cigarette smoking, including nicotine inhalation, render most quit attempts unsuccessful. Recommended therapies, including combinations of counselling and medication, produce long-term continuous abstinence rates of no more than 30%. Thus, more effective treatment options are needed. An intriguing novel therapeutic concept is vaccination against nicotine. The basic principle of this approach is that, after entering the systemic circulation, a substantial proportion of nicotine can be bound by antibodies. Once bound to antibodies, nicotine is no longer able to cross the blood-brain barrier. As a consequence, the rewarding effects of nicotine are diminished, and relapse to smoking is less likely to occur. Animal studies indicate that antibodies profoundly change the pharmacokinetics of the drug and can interfere with nicotine self-administration and impact on the severity of withdrawal symptoms.

- Best Practices for Comprehensive Tobacco Control Programs

http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/stateandcommunity/best_practices/pdfs/2014/comprehensive.pdf

Abstract: Tobacco use is the single most preventable cause of disease, disability, and death in the United States. Nearly one-half million Americans still die prematurely from tobacco use each year, and more than 16 million Americans suffer from a disease caused by smoking. Despite these risks, approximately 42.1 million U.S. adults currently smoke cigarettes. And the harmful effects of smoking do not end with the smoker. Secondhand smoke exposure causes serious disease and death, and even brief exposure can be harmful to health. Each year, primarily because of exposure to secondhand smoke, an estimated 7,330 nonsmoking Americans die of lung cancer and more than 33,900 die of heart disease. Coupled with this enormous health toll is the significant economic burden. Economic costs attributable to smoking and exposure to secondhand smoke now approach $300 billion annually.

- Tobacco Cessation Works: An Overview Of Best Practices And State Experiences

http://www.tobaccofreekids.org/research/factsheets/pdf/0245.pdf

Abstract: Despite reductions in smoking prevalence since the first Surgeon General’s report on smoking in 1964, approximately 46 million Americans and more than 1.2 billion people worldwide continue to use tobacco.1 Tobacco use takes a huge toll around the world by causing an enormous amount of health problems and related death and suffering. Tobacco cessation consists of a variety of approaches aimed at reducing the toll of tobacco by helping tobacco users to quit. Helping people to quit smoking is important because of the substantial health benefits to those who are able to quit successfully, such as increased longevity and decreased morbidity and mortality from heart disease, cancer, stroke, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Additional Articles and Books published prior to 2003:

- Ahmed NU, Ahmed NS, Bennett CR, Hinds JE. Impact of a Drug Abuse Resistance Education (D.A.R.E.) program in preventing the initiation of cigarette smoking in fifth- and sixth-grade students. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2002;94(4):249–256. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Arnett JJ, Terhanian G. Adolescents' responses to cigarette advertisements: Links between exposure, liking, and the appeal of smoking. Tobacco Control. 1998;7:129–133. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Black DR, Tobler NS, Sciacca JP. Peer helping/involvement: An efficacious way to meet the challenge of reducing alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use among youth? Journal of School Health. 1998;68(3):87–93.[PubMed]

- Botvin GJ. Preventing drug abuse in schools: Social and competence enhancement approaches targeting individual-level etiologic factors. Addictive Behaviors. 2000;25(6):887–897. [PubMed]

- Brown JH. Youth, drugs, and resilience education. Journal of Drug Education. 2001;31(1):83–122. [PubMed]

- Bruvold WH. A meta-analysis of adolescent smoking prevention programs. American Journal of Public Health. 1993;83(6):872–880. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Burt RD, Peterson AV. Smoking cessation among high school seniors. Preventive Medicine. 1998;27:319–327. [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tobacco use prevention curriculum and evaluation fact sheets.1999b. Available:http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dash/rtc/tob-curric.htm.

- Cummings KM, Hyland A, Pechacek TF, Orlandi M, Lynn WR. Comparison of recent trends in adolescent and adult cigarette smoking behavior and brand preferences. Tobacco Control. 1997;6(Suppl 2):S31–S37.[PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Feighery E, Borzekowski DL, Schooler C, Flora J. Seeing, wanting, owning: The relationship between receptivity to tobacco marketing and smoking susceptibility in young people. Tobacco Control. 1998;7:123–128. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Flay BR, Hu FB, Richardson J. Psychosocial predictors of different stages of cigarette smoking among high school students. Preventive Medicine. 1998;27:A9–A18. [PubMed]

- Glantz SA. Editorial: Preventing tobacco use. The youth access trap. American Journal of Public Health.1996;86(2):1156–1158. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hurt RD, Croghan GA, Beede SD, Wolter TD, Croghan IT, Patten CA. Nicotine patch therapy in 101 adolescent smokers: Efficacy, withdrawal symptom relief, and carbon monoxide and plasma cotinine levels. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2000;154(1):31–37. [PubMed]

- Jacobson PD, Lantz PM, Warner KE, Wasserman J, Pollack HA, Ahlstrom AK. Combating teen smoking: Research and policy strategies. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press; 2001.

- Johnson PB, Boles SM, Vaughan R, Kleber HD. The co-occurrence of smoking and binge drinking in adolescents. Addictive Behaviors. 2000;25(5):779–783. [PubMed]

- Lantz PM, Jacobson PD, Warner KE, Wasserman J, Pollack HA, Berson J, Ahlstrom A. Investing in youth tobacco control: A review of smoking prevention and control strategies. Tobacco Control. 2000 March;9:47–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mermelstein R. Innovative approaches to youth tobacco control: Teen smoking cessation; Unpublished manuscript presented at Innovations in Youth Tobacco Control Conference; Santa Fe, NM. Jul, 2002.Monitoring the Future website. Aug 30, 2002. Available: http://monitoringthefuture.org.

- Pinilla J, Gonzalez B, Barber P, Santana Y. Smoking in young adolescents: An approach with multilevel discrete choice models. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2002;56:227–232. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Richter L, Richter DM. Exposure to parental tobacco and alcohol use: Effects on children's health and development. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2001;71(2):182–203. [PubMed]

- Schooler C, Feighery E, Flora JA. Seventh graders' self-reported exposure to cigarette marketing and its relationship to their smoking behavior. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86:1216–2121. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Stead LF, Lancaster R. A systematic review of interventions for preventing tobacco sales to minors. Tobacco Control. 2000;9(2):169–176. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sussman S. Effects of sixty-six adolescent tobacco use cessation trials and seventeen prospective studies of self-initiated quitting. Tobacco Induced Disease. 2002;1(1):35–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wakefield M, Chaloupka F. Effectiveness of comprehensive tobacco control programmes in reducing teenage smoking in the USA. Tobacco Control. 2000;9(2):177–186. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wakefield MA, Chaloupka FJ, Kaufman NJ, Orleans CT, Barker DC, Ruel E. Effect of restrictions on smoking at home, at school, and in public places on teenage smoking: Cross sectional study. British Medical Journal. 2000 August;321:333–337. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wakefield M, Giovino G. Teen penalties for tobacco possession, use and purchase: Evidence and issues; Unpublished manuscript presented at Innovations in Youth Tobacco Control Conference; Santa Fe, NM. Jul, 2002. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

[1] http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/health_effects/effects_cig_smoking/

[2] http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/health_effects/effects_cig_smoking/

[3] http://services.aarc.org/source/DownloadDocument/Downloaddocs/12.03.1238.pdf

[4] http://www.lung.org/stop-smoking/tobacco-control-advocacy/federal/fda-regulates-tobacco/what-fda-regulation-of.html

[5] http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/50-years-of-progress/fact-sheet.html